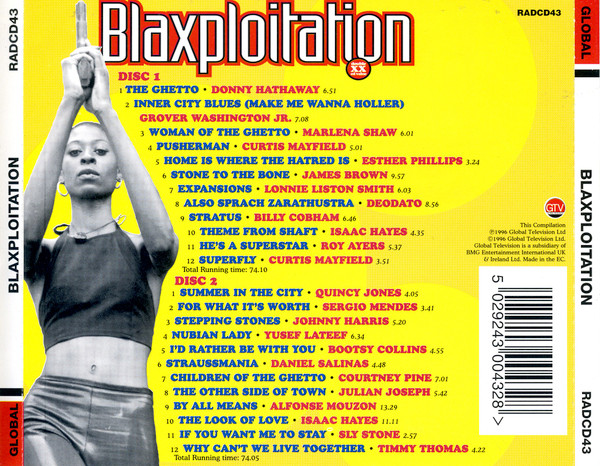

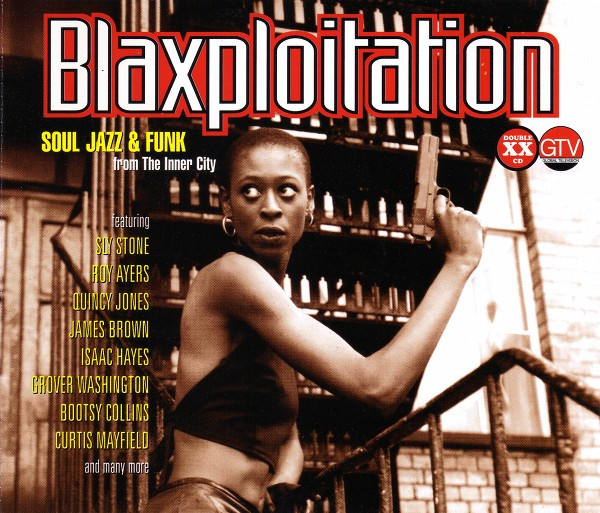

Blaxploitation: Volume One

Given their contemporary kudos, you would think that Blaxploitation movies and their funky, urban soundtracks were everywhere in the early seventies, wouldn't you? Well, yes and no - Isaac Hayes' now-iconic Theme From Shaft was a hit and Curtis Mayfield was achieving enough success to make his soundtrack, Superfly, a hit too. Sure, squealing tyres and depressing inner-city urban crime scenes, along with flashy, wide-lapelled black "pimp" stereotype characters, were finding their way into mainstream cop shows and it was de rigeur to put a little funk in your trunk if you were composing a bit of background music for Kojak or Ironside. However, the movies themselves and their soundtracks - save for those two I mentioned earlier - remained decidedly underground, little-known until they became popular in the late nineties.

What was remarkable, however, was that the influence of those mainly 'b' movies and their soundtracks was huge on both music and wider culture in general. Huggy Bear caricature-style characters sprung up with regularity and, as I was mentioning, the soundtrack to many an urban-based movie was a funky one. String-based instrumentals were augmented by wah-wah guitar, hi-hat and clavinet. The ghetto sound was becoming the blueprint.

Anyway, let's get on with the music, shall we? Can you dig it?

What we get here is not, as you may think, one movie soundtrack after another, but more of an overall feel, as soundtrack themes mixed with funk, soul and jazz fusion workouts to give us the bubblin' cookin' sound that would become known by the name of that movie sub-genre - Blaxploitation.

We begin with a pounder of semi-instrumental funk in Donny Hathaway's The Ghetto, with a few deep cries of "the ghetto" and several "sho' 'nuffs" form the basis of most of the tune's sparse lyrics. Does that matter? Hell no. It was the vibe, man, and this cut is full of it from the off.

The early seventies were when Motown went "aware" and this is reflected here in Grover Washington Jr.'s saxophone-drive interpretation of Marvin Gaye's Inner City Blues (Make Me Wanna Holler). Two better numbers to set the scene you couldn't have asked for.

After that it is time to get some killer vocal songs, ones that expressed what (mainly) US urban, inner-city life was like for (mainly) its disenfranchised poor black population. These are Marlena Shaw's magnificent brooding Woman Of The Ghetto, Esther Phillips' even more hard-hitting (excuse the tasteless pun) and disturbing Home Is Where The Hatred Is. Both of these songs are superbly atmospheric, evocative and pull no punches in either their delivery or their lyrics.

"Strong, true - my eyes ain't blue - I am the woman of the ghetto".

In between these two is sandwiched Curtis Mayfield's ode to puffed-up drug-dealers everywhere in the superbly gritty and funky Pusherman. Check out that bass and percussion intro before Curtis's sweet vocal belies the depressing message of the song. Or maybe the fact that he tells us he is our pusherman in such an attractive style is what the song is all about. A diabolic character who is sadly hard to resist.

Now that these two sisters and one brother have told it like it is, man, we need to immerse ourselves in some pure funk and The Godfather James Brown duly gives us some in Stone To The Bone, expanded here in an effortless groove.

Talking of grooves - jazz "fusion" was a big part of this music's recipe and three lengthy, largely instrumental ingredients are next in Lonnie Liston Smith's Expansions, Deodato's spacey funkster Also Sprach Zarathustra (a track I remember being a hit in its single format in 1973) and Billy Cobham's bassily beautiful Stratus.

We can't escape from the quintessence for long, though, and the guv'nor Issac Hayes is soon upon us with Theme From Shaft - the tale of a complicated man who is only understood by his woman - like me. Far more people heard the theme than ever watched the movie, I'm sure.

Roy Ayers' He's A Superstar is classic Blax wah-wah, bass, flute and rhythm. Over this groove is narrated a religious, spiritual message for the times. A similar such message is conveyed in Curtis Mayfield's classic of the sub-genre, Superfly, but this guy ain't no Messiah, no sir. This guy, for all his posturing braggadocio, is the very lowest of the low. Glamorise him at your peril.

As we flip over to disc two, it's fusion time again, with Quincy Jones' laid-back, chill-out version of the Lovin' Spoonful's Summer In The City, a version which is not really recognisable as a cover of that song. Not for me anyway. The vocal part of the song does make it more familiar though. Either way, it brings some late-night smooth groove to proceedings.

Sergio Mendes gives us a stonker of a cover in a Brazilian jazz meets urban funk version of Buffalo Springfield's For What It's Worth, a song redolent of riots and student demonstrations in the late sixties. It suits this album and its themes perfectly.

Johnny Harris' frantic flute and drums-based rhythmic freakout Stepping Stones and Yusef Lateef's blissful Nubian Lady are two quality instrumentals, different in pace but both ideal for this collection. They are examples of how movie soundtracks influenced other music. Both could easily have been part of a soundtrack.

Funkadelic-Parliament collaborator Bootsy Collins features here on a smoochy piece of sensual funk in I'd Rather Be With You. In many respects this track's sound is the heaviest cut of slow funk on here. In contrast Daniel Salinas' Straussmania funks up classical music with serious hints of Deodato's Also Sprach Zarathustra in there. It is also, in a different way, funky as fuck. Listen to those keyboards.

Jazzer Courtney Pine on the tasteful sax and his vocalist (I'm not sure who) are responsible for a jazzy and soulful number in Children Of The Ghetto, song whose light beauty detracts slightly from its message. Julian Joseph's The Other Side Of Town is very Curtis Mayfield-esque in everything about it. Love the saxophone on it too, and the bass-piano interaction for that matter. This album is not all about gritty urban soundscapes. There is some beauty here too, for sure.

Now it is the business end of the collection - two lengthy numbers in Alphonse Mouzon's almost disco strings 'n' sax-enhanced groove By All Means followed by Issac Hayes' drawn-out piece of seduction in The Look Of Love. Once again, not a pusherman to be found here - maybe that is a good thing. There is musical hope in this album's overall message.

This excellent album ends with a couple of quirky choices - Sly & the Family Stone's short soul-funk number If You Want Me To Stay and Timmy Thomas's musically minimalist plea for unity in Why Can't We Together - a superb track that I also remember from its time in the UK charts in 1973. It is a fine closer - arguably the best track on the album. Get a load of those organ breaks.

As I said earlier - Can you dig it? Right on you can.